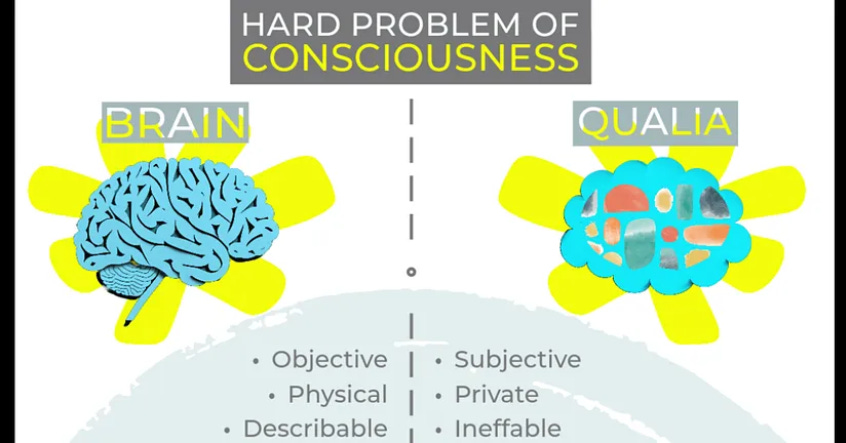

Explaining Qualia?

“The problem of explaining these phenomenal qualities is just the problem of explaining consciousness. This is the really hard part of the mind-body problem.”— David Chalmers

What does the Australian philosopher David Chalmers mean by the the word “explaining” (as in “explaining consciousness”)? That is, what is it to explain qualia or to explain consciousness?

What would an explanation of phenomenal qualities look like — even if there is one… somewhere?

This isn’t to say that there is — or there isn’t — an explanation: it’s simply to ask what such an explanation would look like.

More particularly, it can be suspected that no explanation would ever satisfy David Chalmers… or any other non-physicalist for that matter. And that could quite possibly be because there can be no explanation which pleases everyone — at least not of the kind that Chalmers demands.

Perhaps this is, after all, a bogus problem.

What does that mean?

It means that the Hard Problem isn’t a problem at all. [I’ve gone into this in greater detail elsewhere. See here and here.] Either that, or no explanation would ever satisfy all those philosophers who’re demanding an explanation.

More technically, would such an explanation of phenomenal properties be an explanation from a first-person (or subjective) point of view?…

Well, that wouldn’t satisfy many scientists and philosophers.

Okay.

Would such an explanation be a neuroscientific (or behaviourist or functionalist) explanation?…

Well, that wouldn’t satisfy Chalmers and many other philosophers.

So what about uniting these physical (or functional) accounts with first-person accounts?

Is that possible?

Well, Chalmers gave it a try with his notion of “structural coherence”.

But, firstly, the British neuroscientist Anil Seth (kind of) hinted at structural coherence when he recently wrote the following words:

“[I]f we instead move beyond establishing correlations to discover explanations that connect properties of neural mechanisms to properties of subjective experience [] then this gap will narrow and might even disappear entirely.”

David Chalmers himself tackled this issue many years ago — i.e., in 1995. So, 29 years ago, Chalmers wrote:

“This is a principle of coherence between the *structure of consciousness* and the *structure of awareness*.”

Yet, later, Chalmers also notes the problems here:

“This principle reflects the central fact even though cognitive processes do not conceptually entail facts about conscious experience [and] not all properties of experience are structural properties.”

Simply put: we can say that if x is coherent with y, then x and y still can’t be one and the same thing. Thus, we don’t have any literal identity here…

So doesn’t the Hard Problem remain?

What about the many and varied verbal reports of consciousness and/or qualia?

A person may verbally report his experience/s of particular phenomenal properties, and that might well have satisfied, say, Daniel Dennett. [See here.] However, and so the argument will go, such reports would still only be verbal reports of qualia — not accounts of qualia themselves (whatever that may mean!).

What’s more, perhaps even if there were such an account of qualia themselves, then it still couldn’t — almost by definition — be united with a scientific account.

Thus, there’s both a definitional gap and an “explanatory gap” between scientific accounts of phenomenal properties, and the subjective (or first-person) accounts of the (supposedly) very same things — and never the twain shall meet.

Chalmers will argue that the (or his) Hard Problem remains.

The upshot here is that David Chalmers will never be satisfied with the accounts of Daniel Dennett, (many) scientists, etc. And Dennett and these scientists will never be satisfied with the accounts of Chalmers and the “mysterians”.

Again, there’s a large gap between the two positions.

What’s more, even those much-advocated structural correlations (i.e., between neural states and conscious states), and Chalmers’ own (stronger?) notion of structural coherence, will never bridge that gap…

Perhaps nothing will.

Perhaps nothing can.